Innovate Articles

Defining a Claim: How Design Patent Drawings Can Strengthen or Spoil Your Application

Yitzchak Besser

The right drawing in a design patent application refines the scope and definition of an applicant’s claim. Using an inadequate, indefinite, or unclear drawing can result in a loss during litigation over patent infringement.

Consider the recent Federal Circuit case of Curver Luxembourg, SARL v. Home Expressions Inc.[2] Curver applied for and received a design patent using drawings in which a particular interwoven Y-shaped pattern was represented. The drawings depicted only the pattern and not a specific article of manufacture. Note that an “article of manufacture” is required under 35 U.S.C. § 171.

Curver’s patent is titled “Pattern for a Chair.” Curver asserted the patent against Home Expressions, which produced and sold laundry baskets with a pattern similar to the one depicted in Curver’s patent. To be clear, Curver alleged in their lawsuit that Home Expressions’ baskets infringed on Curver’s patent for chairs.

In their defense, Home Expressions argued that their baskets couldn’t infringe Curver’s design patent because that patent was limited to chairs. The district court agreed with that assessment, and construed the scope of Curver’s patent as being limited to the illustrated pattern only when applied to chairs.[3]

Curver challenged this decision, but lost in court again at the appellate level.[4] The Federal Circuit found that Curver was attempting to broaden significantly the scope of their design patent.[5]

“Curver’s argument effectively collapses to a request for a patent on a surface ornamentation design per se. As Curver itself acknowledges, our law has never sanctioned granting a design patent for a surface ornamentation in the abstract such that the patent’s scope encompasses every possible article of manufacture to which the surface ornamentation is applied… We decline to construe the scope of a design patent so broadly here merely because the referenced article of manufacture appears in the claim language, rather than the figures.”[6]

This case demonstrates the need for a well-defined drawing, one that applies a shape, configuration, or surface ornamentation to a specific article of manufacture. Applicants cannot simply attempt to claim a pattern “in the abstract” so as to cover every possible article of manufacture.

Going forward, one should be mindful of describing the invention in the words and title, as well as the drawings. Without such wording, “abstracted” drawings will likely be rejected by the USPTO. Similarly, patents with disassociated drawings and indefinite wording can be expected to fall short in any patent infringement litigation, as was the case in Curver.

While drawings in design patent applications cannot have infinite possibilities, that does not mean that they are limited to only a single possibility either. This is because courts have been willing to hold that a single design patent drawing can cover multiple interpretations.

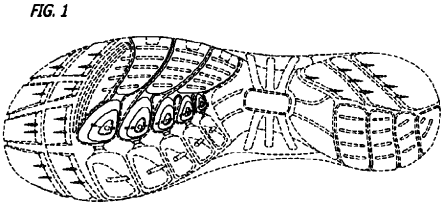

One prominent example of this claim-construction flexibility is found in the Federal Circuit case of In re Maatita.[7] The case involved a two-dimensional drawing of the sole of a shoe as the only depiction included in the design patent application.

The drawing featured a series of similarly shaped rings nested inside of one another. Those shaped rings suggested depth and contour, but the two-dimensional depiction of the drawing inhibits a definitive understanding of the three-dimensional nature of the design. With this in mind, the patent examiner rejected Maatita’s application, noting that it “left the design open to multiple interpretations regarding the depth and contour of the claimed elements, therefore rendering the claim not enabled and indefinite.”[8]

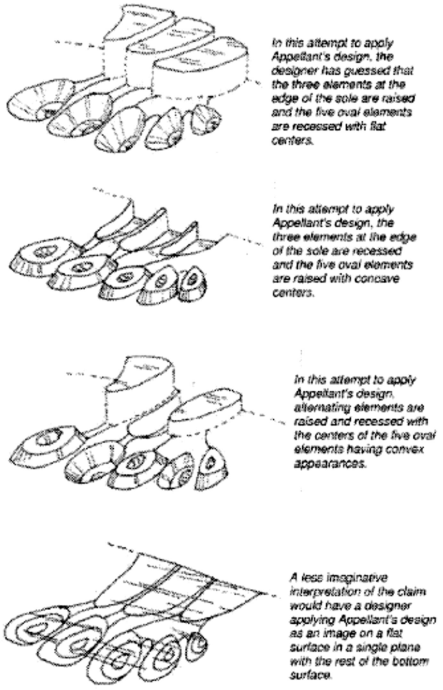

To emphasize the point, the examiner prepared four three-dimensional renderings of Maatita’s two-dimensional drawing. Each of the examiner’s renderings depicted an allegedly different implementation of Maatita’s design. The examiner believed that because each of these four renderings was patentably distinct, they could not be covered by a single claim. Thus, according to the examiner, Maatita’s claim was indefinite, not enabled, and therefore ineligible for a patent.

The Federal Circuit found that a “visual disclosure may be inadequate—and its associated claim indefinite—if it includes multiple, internally inconsistent drawings.”[9] That being said, the court also stated that inconsistencies “do not merit a § 112 rejection, however, if they ‘do not preclude the overall understanding of the drawing as a whole.’”[10]

The key criteria for indefiniteness, the Federal Circuit explained, was whether the “claim, read in light of the visual disclosure…, ‘fail[s] to inform, with reasonable certainty, those skilled in the art about the scope of the invention.’”[11] In other words, the question surrounding indefiniteness is whether “the disclosure is clear enough to give potential competitors (who are skilled in the art) notice of what design is claimed—and therefore what would infringe.”[12]

Under that rubric, “so long as the scope of the invention is clear with reasonable certainty to an ordinary observer, a design patent can disclose multiple embodiments within its single claim and can use multiple drawings to do so.”[13] However, in situations where it is unclear whether a drawing adequately discloses the design of an article, the court held that “the level of detail required should be a function of whether the claimed design for the article is capable of being defined by a two-dimensional, plan- or planar-view illustration.”[14]

In spite of the ambiguity surrounding Maatita’s two-dimensional drawing, the Federal Circuit reversed the examiner’s decision and established the patent eligibility of his claim. In so doing, the court strengthened two-dimensional drawings of three-dimensional articles of manufacture.

Under this ruling, definiteness does not necessarily equate to a single, binding interpretation, as indicated by the examiner’s four three-dimensional renderings. Rather, a design patent with even a single drawing may have multiple interpretations and still be considered “definite” enough for the purposes of patent eligibility.

Consequently, a single drawing may cover a myriad of different three-dimensional articles, so long as an ordinary observer can understand the two-dimensional aspect of the claim. All of those different interpretations could be protectable. Under the right circumstances---i.e. a case involving a product that is typically considered at least in part with a planar view, like a rug or a shoe sole---a single drawing can significantly broaden the scope of a claim.

Taking Curver and Maatita together, one can conclude that while a drawing in a design patent application cannot have infinite interpretations, that same drawing is not limited to a single interpretation either. This expansive view of the power of a single drawing extends even to cases that one might consider to be unclear.

Choosing the right drawing and wording is paramount for design patent applications. Ultimately, a single drawing can create a powerful claim. The right drawing can broaden the scope of a design patent. The wrong drawing can destroy it.

[2] Curver Luxembourg, SARL v. Home Expressions Inc., 938 F.3d 1334 (Fed. Cir. 2019)

[3] Id. at 1336.

[4] Id.

[5] Id. at 1339

[6] Id.

[7] In re Maatita, 900 F.3d 1369 (Fed. Cir. 2018)

[8] Id. at 1372.

[9] Id. at 1375.

[10] Id. at 1375-76 (quoting Ex Parte Asano, 201 U.S.P.Q. 315, 317 (Pat. & Tr. Office Bd. App. 1978)

[11] Id. at 1376 (quoting Nautilus, Inc. v. Biosig Instruments, Inc., 572 U.S. 898, 898-99 (2014).

[12] Id.

[13] Id. at 1377.

[14] Id. at 1378.

The author is a 3L student at the University of Baltimore School of Law and an extern at Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman LLP. He would like to thank Mr. William Atkins for his guidance throughout this externship experience. A former journalist and content director, Mr. Besser has been published in a number of outlets, including The Jerusalem Post, IPWatchdog, and the digital platform for the University of Baltimore Law Review. Likewise, a forthcoming edition of the Journal of the Patent and Trademark Office Society will include one of Mr. Besser’s articles.